If you have ever moved from the place you spent most of your life in, especially your early years, to another place, then you usually experience a deep longing for what you lost. This desire for the familiar, for the place you belong is called homesickness. It usually takes up all our attention and won’t leave until we have adapted or returned home, but some homes cannot be fully adapted to.

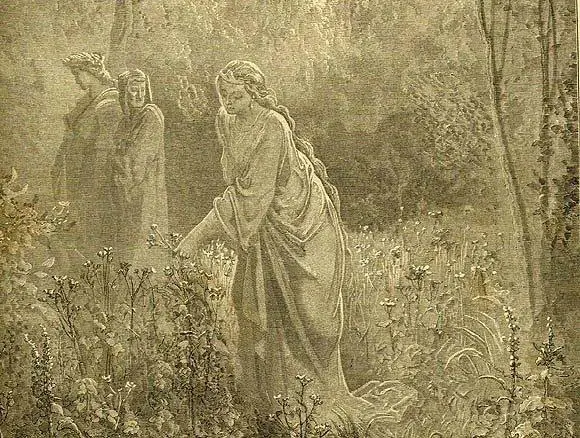

The Earthly Paradise, Eden, was the true home of man on earth. It’s not the final destination, but Eden was meant to be our temporary home. As fallen creatures, we will not know what the Earthly Paradise was like, but we still pine for the state of innocence, we still pine for the peace of our passions, and we still pine for the “gentle breeze” of our should-have-been home. When Dante had ventured into the “Sacred wood,” he was lost. “Now, when my footsteps, slowly as they fell, so far within the ancient wood were set that where I’d first come in I could not tell…” (28.22-24). The desire for home in the heart of man and the echo of Eden in poetry do not fully let us know our old home, but they deepen our desire for its creator.

The “Garden of Eden” is the common name for the Earthly Paradise, but Dante calls it the Sacred Wood. The Earthly Paradise is no longer a garden because it no longer has its intended gardener: man. Dante expresses this sense of loss through the remembrance of a pagan story: “O thou dost put me to remembering of who and what were lost, that day her mother lost Proserpine, and she the flowers of spring” (28.49-51). Even the pagans remember the loss of spring and life.

Dante is met in this wood by a woman named Matilda; the notes give many explanations for her existence, but I believe that she is an image of what this life of innocence would be like. She is carefree: some of the most carefree and content activities I can think of, which she does, are singing and simply picking flowers, enjoying creation. We are not told whether she has ever been in Heaven, but her love and beauty as described by Dante give us a taste of what our life could have been like: “Never, for sure, did such bright radiance glance from Venus’ eyelids, when her wayward child had pierced her with his dart by strange mischance” (28.64-66). Matilda has a perfectly ordered love for this paradise in creation and for Dante. She is content.

The Earthly Paradise was only a foretaste of the Heavenly Paradise: “The most high Good, that his whole self doth please, making men good, and for good, set him in this place as earnest of eternal peace” (28.91-93). God gave man the grace of earthly paradise as a home before his real home. Man was at peace there, for a short while, but instead of being content with what was given him and what would have been given him, he rebelled. The sons of Adam are now given only an echo, a daydream, and a breeze of their home: “Those men of yore who sang the golden time and all its happy state—maybe indeed they on Parnassus dreamed of this fair place” (28.139-141). What was lost is still remembered, and one of the most bitter things to lose is your home. But these men sang, because of their homesickness, of their should-have-been home, for one of the greatest joys and sorrows in life is reminiscing and daydreaming about something that was good and beautiful but will never return.

This echo of the Earthly Paradise has sounded through the ages through art, myth, and song: “Here was the innocent root of all man’s seed; here spring is endless, here all fruits are, here the nectar is, which runs in all there rede” (28.142-144). Man has called on this echo or Muse to influence his storytelling, for the breeze of the Sacred Wood reaches the heart of man. After Matilda spoke the above words, Dante looked back at “my poets standing in the rear” (28.145). C.S. Lewis describes this echo beautifully and gives a perfect reason for Virgil knowing this echo in his work Perelandra: “Memory passes through the womb and hovers in the air. The Muse is a real thing. A faint breath, as Virgil says, reaches even the late generations. Our mythology is based on a solider reality than we dream: but it is also at an infinite distance from that base” (172-173). The Muse is real. Sin was passed on to all of Adam’s descendants and, with it, the memory of our lost home. This desire for innocence, this memory of home, this dream of Eden, and this breeze of the Sacred Wood is the Muse of Homer, Virgil, and Dante. Mythology is not reality, but it sometimes gives a clearer picture of reality than our senses and thoughts on their own. But the Earthly Paradise was never meant to fully satisfy man; it was only to be seen as the launch pad for eternal life in the presence of God. The countdown of a launch is only ten seconds, but the time spent waiting for eternity is far less in comparison.

Dante has climbed mount purgatory and finds what man lost. Dante has the seven deadly sins wiped from his forehead, and he arrives at the place all mankind could have already been. We cannot live in this Earthly Paradise, but the desire for it is not useless. Just as our first parents looked at this place and were reminded of God and his love, its memory can do the same. The memory of Eden reminds us of and directs us towards God, because no Earthly Paradise, no matter how beautiful, will satisfy man. Only when man “dwells in the house of the Lord” (Psalm 27:4) will he be content.