“Faith therefore has no fear of reason, but seeks it out and has trust in it. Just as faith builds on nature and brings it to fulfillment, so faith builds upon and perfects reason.”

Reason, according to St. Thomas Aquinas, is man’s most excellent activity. It is the activity that turns our eyes to God, that builds empires, that secures communities. And yet, despite having this great power, it seems most people would prefer not to have it at all. There is no… inspiration. No fire, no desire to be educated, a gift that, at one time, was sought out with the utmost desperation. Women fought to be educated in Universities, slaves were killed for learning how to read. You would think that such a coveted gift would be beyond celebrated in a world like today, where kids are expected to start school as young as six months old. But today, school is dull. It’s repetitive, tedious, and even in some cases, almost unnecessary.

There was a time when, as Pope St. John Paul II said at the beginning of this inquiry, everyone understood that reason is inextricably linked to faith. That our rational world is so much deeper than what we can see and comprehend. This once inspired people to get as much of an understanding of it all possible in their lives—but we are so apathetic now. And my guess is that it has to do with how it has been presented to us.

Ask any high school kid coming out of his science class what the purpose of an acorn is, and he’ll probably say to grow a tree. Ask him to explain deeper and he’ll probably short circuit. The way we are taught to look at the world is so… mechanistic. It’s drab, it’s lifeless, it’s demoralizing. So the question then is: when did this all start? When did nature lose its Beauty? When did people stop connecting reason with faith? Well, the Scientific Revolution. The Scientific Revolution fundamentally reshaped the landscape of scientific thought, moving away from older models and establishing new methodologies and philosophical underpinnings that continue to influence how we understand science today.

I conclude, therefore, that the Scientific Revolution, having conquered Greece, has negatively impacted the dominant Western understandings of how the youth ought to be taught natural science. I intend to examine this trend by comparing the modern methodology of teaching science, and the attitudes that come with it, to those of the Medieval and Enlightenment eras. By examining how education has changed through these eras, I intend to prove that the ideologies that propagated because of the Scientific Revolution have worsened, or even destroyed, how the West teaches natural science to the youth.

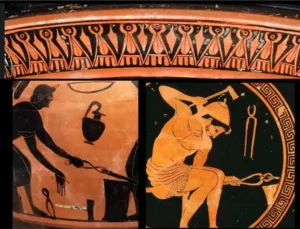

During the European Middle Ages, scientific inquiry, known at the time as natural philosophy, was seen as inseparable from theological and philosophical thought. The Medieval era had a different understanding of “natural philosophy” than we do, which was heavily influenced by ancient Greek education culture. St. Thomas Aquinas was a great admirer of Aristotle, and also saw his method of scientific study as the ideal. As stated in the introduction of The Division and Methods of the Sciences:

For [St. Thomas], science in general is knowledge of things through their causes. As Aristotle said before him, it is knowledge not only of fact, but of reasoned fact. It reaches its ideal, not simply when it records observable connections in nature and calculates them in mathematical terms, but rather when it accounts for observable phenomena and the properties of things by bringing to light their intelligible relations to their causes.

Medieval students were taught to ask four types of questions about things in nature, and nature itself: What is it made of? What is its form or essence? What is its cause (aside from the obvious, ultimate answer)? And crucially—what is its purpose? These are Aristotle’s four causes, which served as the foundation of scientific inquiry at the time.

Now, to give a little diversity of thought, St. Thomas’ mentor, St. Albert the Great, while an Aristotelian, was not dogmatic. He emphasized the need for nuance towards Aristotelian thinking, as Aristotle, being human, could err. He argued that to have good theology you need good philosophy, which needs good natural science, as the medievals believed that the three subjects were inextricably tied together.

Before moving onto the Enlightenment, it is important to mention the Galileo Affair—not because of the specifics of his conflict with the Church, but because of its cultural impact. The conflict stemmed from Galileo’s promotion of Copernicus’ heliocentric theory, with historically bad timing. Martin Luther had made a significant impact on the faithful, which made all criticism of the Church, and dissociation from Her, extremely popular. The controversy helped establish a narrative that faith and reason were fundamentally opposed, that the Church was anti-science, and that true inquiry required separation from religious authority. Unfortunately, this feud with Galileo only made that flame grow brighter, and trust in the Church’s ability to teach anything took a significant blow.

In sum, the whole inclination and bent of those times was rather towards copy than weight. Here therefore in the first distemper of learning, when men study words and not matter, whereof though I have represented an example of [Medieval] times, yet it hath been and will be secundum maius et minus.

So expresses Francis Bacon, the creator of the modern scientific method, in his essay The Advancement of Learning: The Abuses of Language. When Bacon wrote this, he was not only expressing his own opinion, but that of many Western scholars at the time. And so began… the Enlightenment. *Thunder*. It was around this time, in the mid-seventeenth century, that it became fashionable to separate faith from all natural philosophical practices. Thomas Browne captures this growing tension between scientific study and religious faith in Part 1 of his Religio Medici:

For my religion, though there be several circumstances that might persuade the world I have none at all—as the general scandal of my profession [as a physician/natural philosopher], the natural course of my studies, the indifferency of my behavior and discourse in matters of religion, neither violently defending one, nor with that common ardor and contention opposing another—yet in despite hereof I dare without usurpation assume the honorable style of a Christian.

Of the diverse group of Scientific Revolutionaries, many actively contributed to a methodological shift which fundamentally altered the perception and study of nature, despite their personal faith. The most famous of these would be René Descartes, who rejected Aristotelian metaphysics, epistemology, and the reliance on ancient texts for scientific understanding. He emphasized reason, common sense, experience, and the mathematical basis of reality.

From Descartes came Isaac Newton, who also proposed a universal law of nature that governs how all material things operate. He then went on to develop calculus to study rates of change and extensively used mathematical proofs in his Principia to explain his laws, confirming and extending Descartes’ belief in the mathematical basis of the universe. The moderns, laying aside substantial forms and occult qualities, have endeavoured to subject the phenomena of nature to the laws of mathematics. This single sentence announces the death of Greece in Western education. The “substantial forms” and “occult qualities” were not refined or corrected—they were laid aside entirely, replaced with mathematical laws that could explain how but never why.

This emerging scientific paradigm significantly narrowed the kinds of questions that could even be asked. That rich, qualitative understanding of the goodness of nature which the medieval philosophers had pursued was rendered inadequate. What emerged in its place? As one admirer of Newton wrote, “Guided by the genius of Newton, we see sphere bound to sphere, body to body, particle to particle, atom to mass, the minutest part to the stupendous whole—each to each, each to all, and all to each—in the mysterious bonds of a ceaseless, reciprocal influence.” The universe became a vast machine, unified, predictable, and explainable. The Scientific Revolution had succeeded in creating a new framework for understanding how nature operates. The question was: what would happen when this mechanistic, reductionist methodology became not just a tool for studying nature, but the very foundation of how we educate the next generation?

By the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the philosophical commitments of the Enlightenment had thoroughly permeated Western education. What began as Descartes’ methodological approach had hardened into an ideology: scientism, the belief that scientific knowledge is the only valid form of knowledge (“we believe only in what we can see and touch”). Combined with the Protestant Reformation’s fracturing of religious authority and the spread of secularism, Western education increasingly removed God from the equation, viewing the universe simply as a giant machine functioning according to fixed, self-predetermined laws. We stopped teaching students to ponder the reason behind something’s existence and how it ties into the Grand Plan, transitioning instead to asking only what the mechanics are and how they are useful to me, myself, and I.

Pope St. John Paul II identified this problem exactly in Fides et Ratio, warning:

It would be misleading to claim that scientific results alone could define the meaning of life and of human existence. Such claims, when they arise, express not science but scientism, a distortion of reason which refuses to recognize its own limits.

The late Pope Francis also wrote about the effect this mentality has on how we teach natural science. In his Laudato Si:

Whereas in the beginning [scientific education] was mainly centered on scientific information, consciousness-raising and prevention of environmental risks, it tends now to include a critique of the ‘myths’ of a modernity grounded in a utilitarian mindset (individualism, unlimited progress, competition, consumerism, the unregulated market). (§210)

The result? Modern students learn reductionism—to just break everything down into parts, without seeing the whole, without considering meaning and purpose. Medieval students studying an acorn learned not only its material composition but its purpose—to become an oak tree, to fulfill its nature, to participate in God’s ordered creation. Modern students can look at that same acorn, and if they paid attention in class they can tell you about the cellulose structures, germination chemistry, and evolutionary advantages, but the beauty of its existence, the romance (so to speak), simply isn’t there. We’ve trained an entire generation of technicians who can explain how things work (the mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell), but who have no framework for asking why things exist (why is a mitochondria?). And that, I believe, is not only a loss for Greece, but the loss of Greece itself.

I mentioned at the beginning how this question came to my mind, but the more important question is: why does it matter? I was telling my brother, my sole insight into the mindset of the average, non-melancholic college student, about this assignment on our way to Thanksgiving with my dad’s family. He asked that question: “why does it matter? Beauty, emotion, needs to stay away from science in order for science to be what it has to be: objective, reasonable.”

When I first started writing this, I was looking at it from the perspective that the Medieval era did natural science the “right” way, or at least in a better way. I guess I’d forgotten literally the entire point of a holistic view of nature. That being the message that, modern scientific insight, and the four causes, have their places together, hand-in-hand. So, what’s my problem, then?

They’re not hand-in-hand, not at all, not even close. We’ve separated them from each other completely, and that has made a generation like my brother. Beauty, or just frivolity, needs to stay with the arts, and the objective stuff needs to stay with the sciences. Separate, never to mix.

Whether we like it or not, how people are educated in childhood defines what the world looks like in adulthood. If we teach kids that science has no need to be guided by beauty, or even truth, that mentality bleeds into other facets of life, even the simplest ones. Language is ugly, architecture is ugly, fashion is ugly, people are ugly—all with the justification that these things need only to be “functional,” not beautiful.

If you, my dear audience, take nothing else from my spiel, take this: Love being educated. Pursue it passionately, and with it, fall in love with your faith. Dress well, speak elegantly, be kind, and remember to appreciate the acorns. Reason has no fear of beauty, but it seeks it out, and has trust in it.